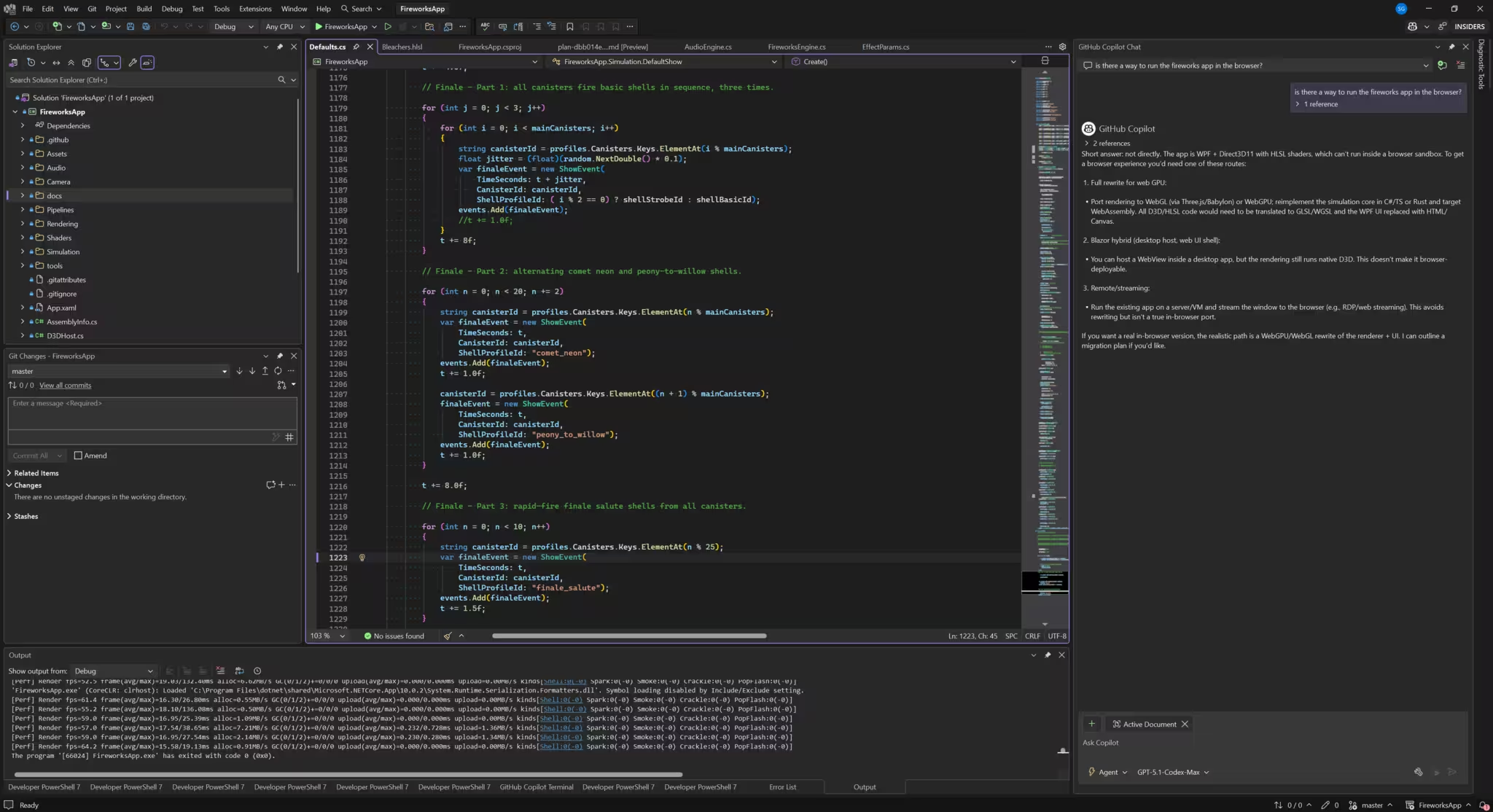

Fireworks Simulation App

Something from my bucket list, a simulator app that generates realistic 3d fireworks shows.

Background

January 1st came around, and with all the cool fireworks displays, it got me to thinking about an old fascination I had with simulation software and fireworks. It has been on my bucket list to write a fireworks simulator for a while, but my software skill-set was more around server side development and video production. I knew a little about game design and GPU coding, just enough to be dangerous. With the advent of AI co-coders like Github Copilot and Codex (from OpenAI, the same folk who brought you ChatGPT), I figured I would give it a try. This post will have some geek aspects to it, since it is largely about writing this app, but I think the non-software engineers out there might fight it interesting as I share some of my take on what it is like to code with an AI assistant (or two or three as you will see).

If you want to play along with any of this, see the app itself or look at the code, it is in a public Github repo here: Fireworks App. A link to the most recent release and installation instructions can be found on the right side. Enjoy!

The Environment

The Platform

I am a C# developer by trade, I spent a good chunk of my career in “devdiv” (developer division at Microsoft) working on developer tools focussed on C# and .NET. It is a great platform, and while I haven’t used enough of the competitor’s platforms to offer a comparison, I know that it works for me, so I was down with that.

Once on the C# path, DirectX seemed the next logical step. There are more sophisticated options out there (the Unreal Engine came up a lot), but it is pretty complex and has a super steep learning curve. The AI recommended DirectX v11 over v12 which was surprising, as it cited a lot of unnecessary complexity in v12. Ok.

Visual Studio was the dev env of choice. As much as I like VS Code, nothing beats the power you get from the full Visual Studio experience when debugging and diving deep.

The AI

I have used Github Copilot a lot over the last couple of years, it is billed as “Your AI pair programmer”, and it is very good at that. There are lots of things I just would not have attempted to do without it, so it was the natural choice here.

As I was proceeding through the development stages however, I decided to add a couple of other AI to the mix, namely ChatGPT and GPT Codex. More details on this below, but in general here is how they were used.

- Github Copilot: Github Copilot did most of the heavy lifting in writing code. It was operating in “Agent Mode” most of the time, which lets it directly modify the code and make changes as it wants. One must keep good point to “undo” however, as CP does gets things wrong occasionally.

- ChatGPT: ChatGPT was used as the conceptual AI, knowing about fireworks at the high level, as well as the high-level code behind it.

- Codex: Codex is OpenAI’s developer centric AI, and it was used as a code review specialist. Sometimes it was also used for a second opinion on complex coding efforts.

Author’s note: I know there is a lot of overlap between these AI and how they are used (ie ChatGPT is sometimes the brains behind GitHub Copilot etc, when I categorize them as above I am referring to the primary UI experience that comes with each of these AI.).

Building the App

So I am going to dive into the creation of the app here, but I am going to focus on how it worked with the AI, as I think a post on my coding efforts might be a tad dry.

Initial Setup

So to get started, I had a conversation with ChatGPT about options. I asked some general question about how this kind of an app might be done, and it put out a list of a bunch of things: stuff gamers use, stuff animators use, stuff simulators use. I was thinking it would guide me to using a “physics engine” or a “particle engine” for some of the work, but ChatGPT thought it was overkill and that we could make it work better and simpler without it. I said “Ok”, and went into Visual Studio to create the app and have Github Copilot (CP from here on in) generate me a skeleton, a code outline if you will that had the right folder structure and placeholders for the moving parts, though all were blank at this point.

Early builds

As mentioned, I am not a gamer or graphics developer, so I spent some time trying to understand what CP had created and how it worked. The code didn’t do much more than open up a blank window at this point, but it did work.

I gave CP the conceptual overview of what I was after, and we started simple, just generating a launch pad for the fireworks, which is really nothing more than a blue square. This took a surprising amount of work since CP and I just were not on the same page. It was training me (indirectly) as much as I was training it.

It took about 1/2 and hour to get rolling, but it was a good investment as I learned how to talk “fireworks simulator” talk to CP. You would not beleive the amount of futzing I had to do just to make the launch pad 10cm thick instead of 0, and I could have easily changed it in the code myself, but I wanted to figure out the process.

We then moved on to building the launch canisters and putting them on the pad. This is where ChatGPT came in as a fireworks expert when I asked it to give me a tutorial on canisters and how they work. I love projects where you learn something about other domains, and this is certainly one of them. I am not a fireworks expert by any means, but I do know the difference in muzzle velocities of an M2 versus an M10 mortar is!

I created a handful of very simple single stage fireworks, modelled them in the app and created “show” that lets you run thru a sequence of launches. It worked well but the physics needed a lot of work, things just didn’t look real.

First major AI usage

Once thing the physics had wrong was timing: things just looked too fast. Even though I had modelled things to scale and was using real physics constants (ie acceleration due to gravity = 9.8m/sec2), but somethings were off. Not sure it was the wind resistance of a real show versus my simulation or what, but things needed to slow down. I wanted to add a factor (like 0.80) somewhere that would slow time down across the board.

Copilot couldn’t get this, no matter what I tried it just couldn’t get it right. The implementation was weird, off. It just didn’t fix the problem it was supposed to. So I zipped up code and gave it to ChatGPT and gave it an explanation of what I had tried with CP, and to my surprise it did not just fix the problem, ChatGPT said

Now I had heard of this before, using one AI to craft a detailed prompt for the other, such prompt engineering has been around for a bit. But here it really popped into my head as to how truly powerful that is. It has become my standard operating procedure.

ChatGPT Prompt Engineering

Here is an example of the process. Here I write the following to ChatGPT (skip to the end of the blue section if you are not interested in prompt engineering, which will be 98% of you.):

We need to add a new profile and maybe a burst shape to the app. This one will be called strobe, and it will start with a peony style sphere of particles sparkling, then inside that sphere 100 or so (configurable) “strobes” will appear. Each strobe subshell will be a sharp small pop of colour (defaulting to white) that is about 2.5cm in radius (configurable) and lasts for only 0.25 seconds (configurable). Strobe subshells have no trail. Since the primary shell will have subshells and its own burst, we should model it on an profile that already has the same properties (like peonytowillow).

Help me write the perfect Copilot prompts for this.

And here is what ChatGPT came back with:

Prompt 1 — Add a new Strobe profile (modeled after PeonyToWillow)

Goal: Define a reusable profile that combines a normal burst and timed subshell strobes.

We need to add a new fireworks profile called “Strobe”.

This profile should be modeled closely on an existing profile that already: • Has a primary shell burst • Spawns subshells • Manages multiple visual phases (e.g., PeonyToWillow or a similar multi-stage profile)

High-level behavior:

- The primary shell launches normally.

- At burst time, it produces a Peony-style spherical burst of sparkling particles.

- Inside that sphere, a configurable number of “strobe subshells” will appear and pop.

Profile structure requirements:

- Name: “strobe”

- Must have both:

- A primary burst definition (Peony-style)

- A subshell definition (strobes)

- Subshells must NOT have trails.

- Subshells must NOT spawn further subshells.

Configuration parameters (with reasonable defaults):

- strobeCount (default ~100)

- strobeColor (default: white)

- strobeRadiusMeters (default: 0.025m) // ~2.5cm

- strobeLifetimeSeconds (default: 0.25s)

- strobeSpawnMode:

- All-at-once at burst time

- OR short randomized delays within the primary burst lifetime

- Primary peony spark lifetime should be longer than the strobe lifetime.

Design guidance:

- Follow the same data layout, naming, and initialization patterns used by PeonyToWillow.

- Reuse existing particle kinds where possible.

- Any new fields added to the profile should be clearly commented as “Strobe-specific”.

- Keep the profile data-driven (no hard-coded constants in update logic).

- Default values should look good without tuning.

Do NOT implement rendering or simulation logic here — this step is only defining the profile and how it wires into existing burst/subshell systems.

Prompt 2 — Implement the Strobe burst behavior

Goal: Define how strobes actually appear and pop during the burst.

We now need to implement the burst behavior for the “Strobe” profile.

Concept:

- The primary shell burst behaves like a Peony (spherical distribution of particles).

- Inside that sphere, multiple strobe subshells appear.

- Each strobe is a very small, very sharp pop of color.

- Strobes have:

- No trail

- Very short lifetime

- Small radius

- High brightness / intensity

- Visually, this should read as rapid internal flashes inside the peony.

Behavior details:

- On primary burst:

- Spawn normal Peony particles (sparkling, spherical).

- Spawn N strobe subshells (configurable).

- Strobe subshells:

- Position: random points distributed inside the peony sphere volume.

- Velocity: near-zero or very small random jitter (they should not fly outward).

- Lifetime: ~0.25 seconds (configurable).

- Radius: ~0.025 meters (configurable).

- Color: configurable, default white.

- Strobes should NOT emit trails.

- Strobes should NOT emit secondary bursts.

Timing options:

- Either:

- Spawn all strobes at burst time, OR

- Slightly stagger spawn times (randomized within a small window) to enhance the strobe effect. Pick whichever fits better with the existing event/burst system.

Implementation guidance:

- Model this after how PeonyToWillow spawns subshells, but:

- Remove any gravity-driven or long-lived motion.

- Remove trail logic.

- Use existing subshell infrastructure (no special-case hacks).

- Ensure strobes are cheap to simulate (short-lived, minimal per-frame work).

- Respect per-kind alive lists and existing performance constraints.

Visual goal:

- The viewer should see a sparkling peony sphere.

- Inside it, rapid bright pinprick flashes that blink in and out.

- No lingering dots, no comet-like motion.

Add comments explaining:

- Why strobes are implemented as subshells.

- Which parts are intentionally different from PeonyToWillow.

Yeah I know that was too much to read and there is no way you should read it. But I put that in here to emphasize the point that from my simple descriptive paragraph, ChatGPT generated a whoppingly detailed prompt, that I then cut and past back into CP.

And it was awesome…

I walked away, made a cup of coffee, and about 20 minutes later came back and CP had done the job. It did it pretty well too, much much better than it would have if I had not refined my prompt thru ChatGPT. Now these always require a bit of tweaking and fine tuning, but over all it did a bang up job. And once in a while CP went off into the weeds or “lost the plot” as they say, but in general it was pretty cool and often it was great at it.

With this awesome new power, I discovered I could take on bolder challenges and try more complicated designs. If they didn’t work, I would either back out the changes, or used what was learned by myself and the AI to make another attempt at it.

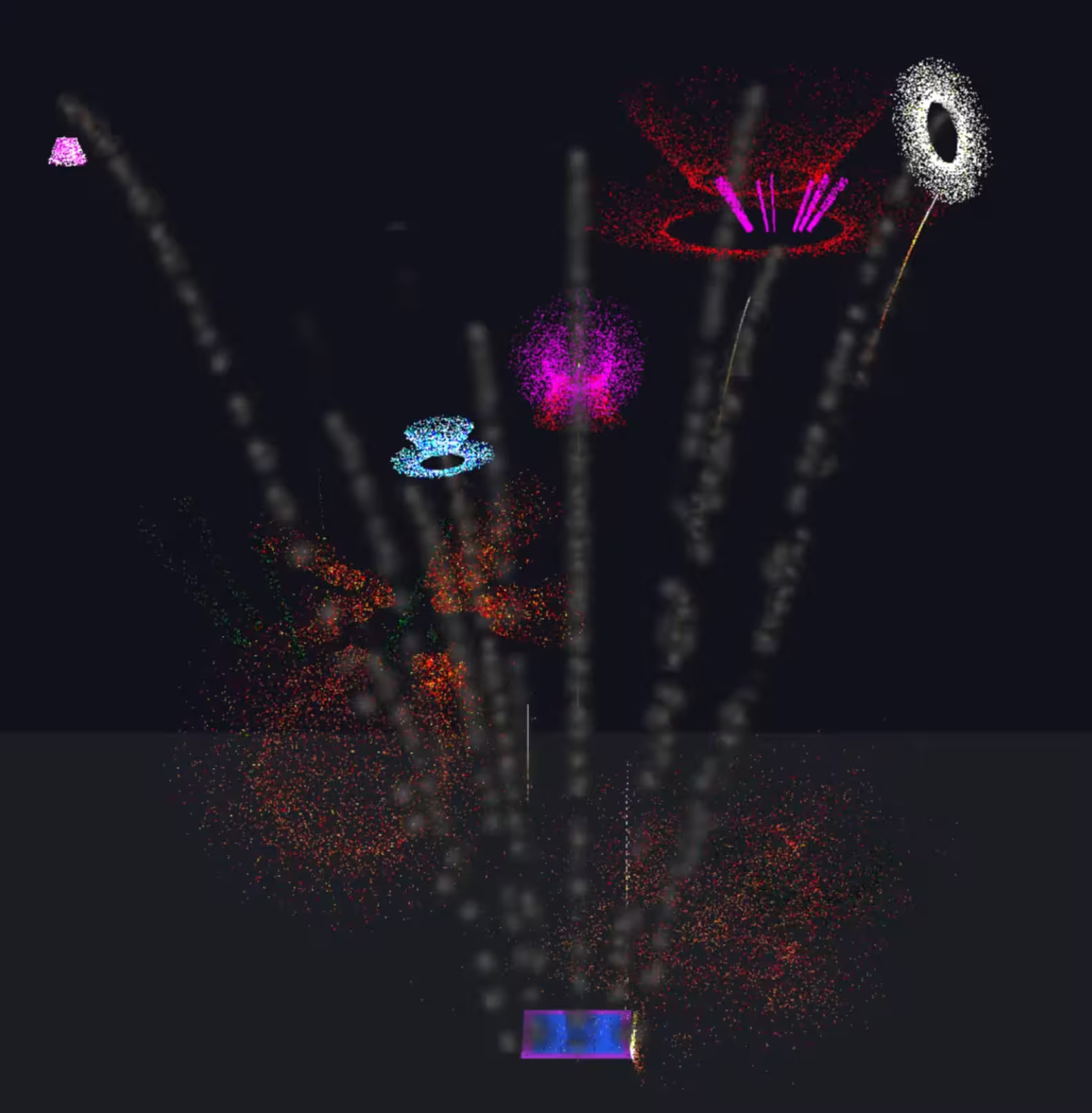

The pic shows the strobe burst embedded in what is called a peony style particle burst. I think the folk in the red parkas in the bleachers really liked it a lot.

Refactoring

Refactoring code, I discovered, is an AI specialty. It is very good at it, but you have to be specific about what you want, else it just makes assumptions and runs around like crazy. Sounds a lot like some former co-workers I used to know (and love).

This can sometimes be tedious work, so it was great to pass it off to the AI and let it do 90 percent of the work. It involves making small files from those that have grown too big over time, redoing naming conventions once patterns have been established etc.

Code Reviews

Another thing that the AI was pretty good at was the code review. I used Codex for this mostly, sometimes ChatGPT. With graphics coding not being my specialty, I had it focus on that, and Codex found things that I would not have found in a million years. It even found massive improvement in performance by casually suggesting “you may want to move this from the CPU to the GPU for better perf”.

And it did it without the attitude you sometimes get from human code reviewers (did I mention that I love my former co-workers).

Thoughts

Here are my thoughts on using the various forms of AI throughout the process.

Context

If I had to use one word always blows my mind about how the AI’s work, it would be context. They understand context. And for the most part they understand it so well that you think you are in a conversation with a human. It is truly amazing. I will give you a small example of what I mean.

At one point in time, I was creating the fireworks show, and that involved laying out the effects and shells that would be used. I created an array of Ids that defined the shells and the order they are to fire in. After I had created the list, I started going thru it putting the comments “Hero” and “not-Hero” beside them so that I could tell which were the bigger more spectacular fireworks from the “filler” kind.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

// Ordered list of shell IDs for the main show. Adjust this list to change launch order.

var mainShowShellIds = new[]

{

shellStrobeId, // Hero

shellSpokeWheelPopId, // Hero

shellDoubleRingId, // not-Hero

shellFishId, // Hero

shellDonutId, // not-Hero

shellWillowHorseId, // Hero

shellCometNeonId, // Hero

shellSilverDragonId, // Hero

shellBlingId, // not-Hero

shellDiamondRingId, // Hero

shellCometCrackleId, // Hero

shellPeonyToWillowId, // Hero

shellSpiralId, // not-Hero

shellChrysId, // Hero

};

The thing is, by the third one, the AI had figured out what I was doing, and it started auto filling-in the comments as I went down the list. There are no obvious markers in the code as to what is Hero and what is not, there is no flag on the effects that says, Hero = true or Hero = false. But the AI got EVERY SINGLE ONE of the remaining 12 Hero/not-Hero comments correct.

There are countless examples of this that I have run across in the construction of the Fireworks Simulator App. Being in the business I have a good idea as to how it is done, still it amazes me to no end.

Time

The second big thing is time. I started this app a little after New Year’s and it took a couple of weeks to get it where I wanted. That time would be measured in months, not weeks, if I had done this without AI. My gut says about three or four months. But to be honest, I am not sure I would have been willing to put that much time and effort into it without AI, so it may never had gotten written in the first place.

Knowledge

The ability of the AI to be a “Graphics Programming Expert” was amazing too. It saved so much search time, looking thru docs etc. I could ask general questions about how something worked on the GPU or DirectX 11, and it almost always had an instantaneously great answer.

The Bad and The Ugly

It was a great experience, but not without its challenges:

- Losing it. Every once in a while, I would say about 1 in 10 times for complex scenarios, both ChatGPT and CP would get lost, or “lost-the-plot” as it were. They were just in never-never-land, and no matter what I said I could not get them out of it, even with my advanced prompt engineering efforts. I would have to “put it down and walk away”…one time CP even agreed that “we should try again later”. Too funny.

- Visuals to code. Describing the visuals behind the fireworks and trying to get that into code can be very trying. It is not easy to get from “starry flaming bursts” to working code. Such is the state of human/machine communications. In some ways though I am impressed that it was able to do it at all, and eventually the AI would get there.

- Nits. There are about 50 “little things” that drive you a little crazy in the workflows. For example, sometimes the AI would resort to writing Powershell scripts to get its job done, but would produce a bunch of errors in its own script when doing so, causing multiple passes to fix it. All of which is going on my bill. Stop it, you should be able to get powershell syntax correct the first time, not need three passes to make it work. There were a lot of things like that.

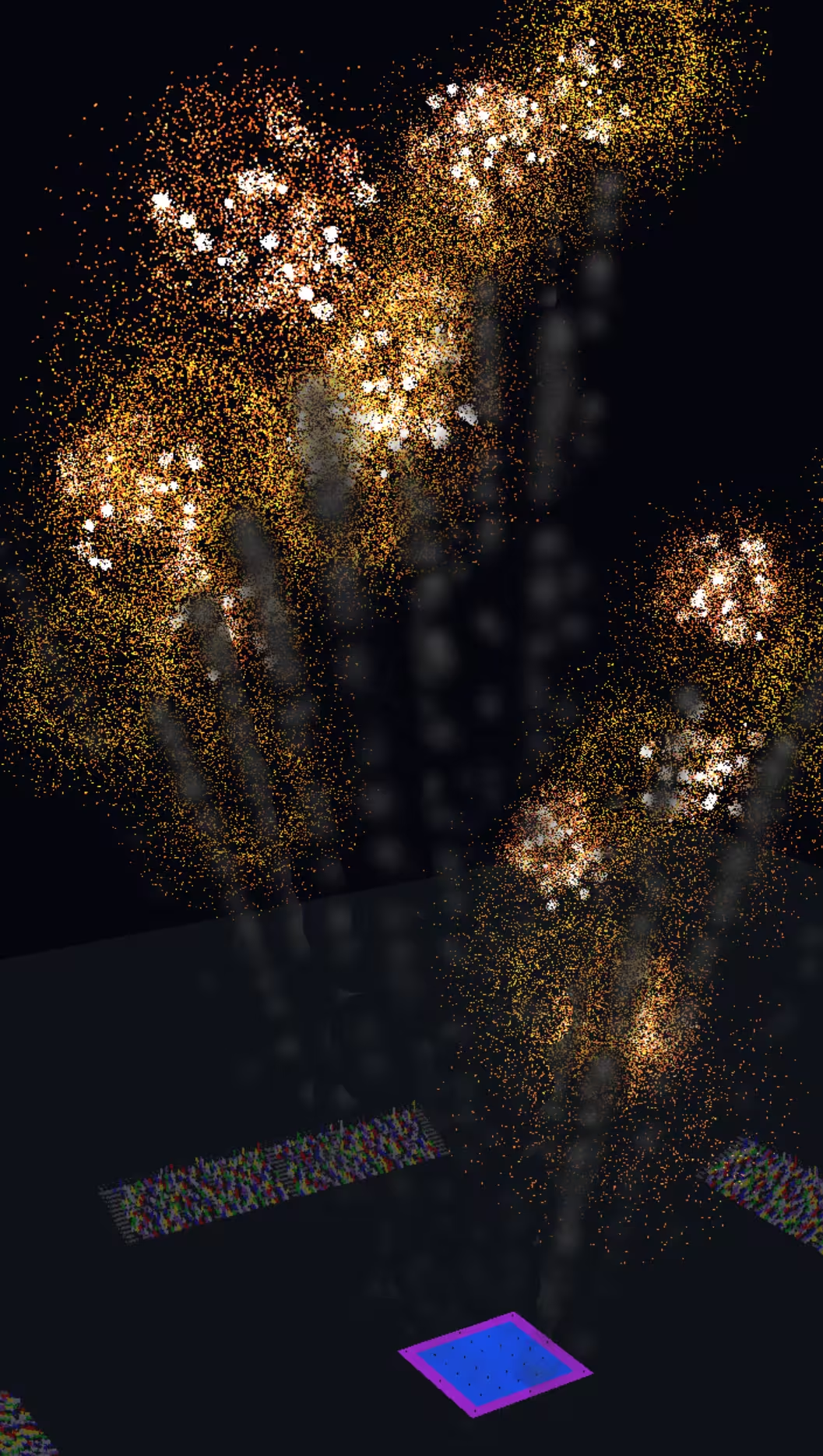

The Finale

Yeah yeah, I hear ya, enough talk, let’s get to the show already. Allright, here is the YouTube video capture of one of the shows I have created.

It has a two minute main show with a one minute finale. It has full 3d camera rotation and sound. Play on.

Resources

- Microsoft Visual Studio

- Github Copilot details can be found here: Github Copilot

- ChatGPT is at OpenAI

- Codex (part of ChatGPT)